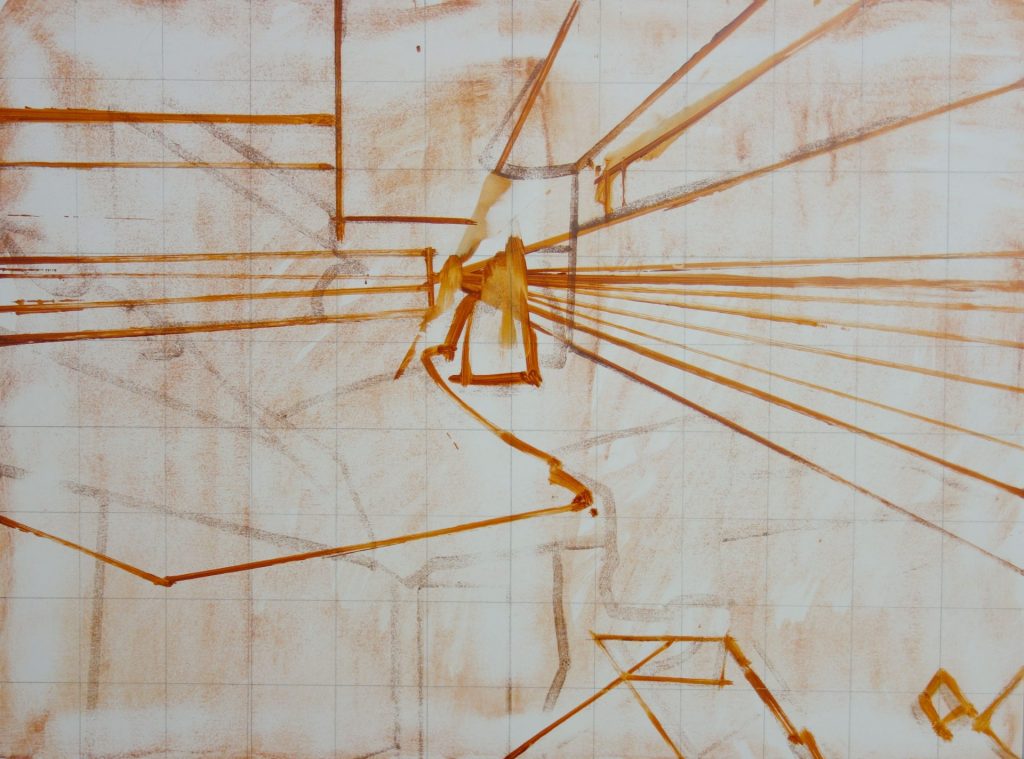

These are time-lapse images for “Lost and Found” from Fascination Street, which, like quite a few others, came very close to being abandoned but ended up being one of my favorite pieces from the show (possibly for that very reason). I’ve realized over the years that documenting my work has become an essential part of my art-making process – so much so that I rarely consider traversing the unknown landscape of a painting without it. I sometimes question this and wonder if it would be better in some ways (or braver) to leave it behind, but the benefits always seem to always snuff out the “what-if’s”. I believe it can make an artist bolder in their decisions because they know they will always have documentation of each phase, which helps to quiet the timid restraint that can result from a fear of losing something you may never get back. It also helps to dispel my own myths about what kind of artist I am and how I work. I can look back and remember that I loathed paintings which I eventually came to appreciate – in fact, the same may be true about the piece I’m stuck on right now. I never had a roadmap, and nobody does. They can only have faith in their abilities to express something that they feel is worth expressing to others.

Lost and Found was a piece that hit multiple walls. It required time away and only moved forward when I couldn’t stand the sight of it’s fixed, taunting expression anymore and had to give it a hard shove in a new direction. It started out with a very different emotional climate than it ended with. What I loved about the memory of the original experience and promised myself I would hold onto (the bright, sun-beaten expansiveness of the dirt covered lot of Gyeongbokgung Palace) eventually went nowhere and disappeared, replaced by an overcast sky and dimmer global lighting. The rekindled enthusiasm for the piece this gave me eventually dwindled as I struggled with composition and concept. I had arrived at portions of the painting that I really loved – that somehow tied in with my own scattered and confused fantasies from childhood – but the the original focal point of the piece (the women in the center) no longer carried it. I felt a huge dead spot in the center and when I stepped back, it felt unresolved and boring. I stepped away for a few months and continued other work, frequently bringing up the most recent image of the piece late at night on my computer. I’d longingly gaze at it and run through possible solutions as if trying to mend a failed relationship. It eventually came – I picked a random color and went at the dead zone with a big round brush, and slowly it became a bridge that seemed to fix everything about the composition for me.

It also seemed to make other problems in my life feel smaller and make me feel more “fixed” outside of the studio, which I find to be a curious and somewhat frightening part of all this. I feel, as I imagine some other artists feel, deeply connected to my work in that way – a symbiotic relationship is formed that can lift me up during times of progress and leave me paralyzed in times of uncertainty. I’ve managed to find ways to temper this connection and create some distance between the two states, but it never leaves completely and probably never will.

The addition of the bridge propelled me forward but once again but left me with the feeling something was missing compositionally. I had played with the idea of the original path the women were on warping and collapsing into the water behind them and attempted bringing this back in with some success. The female figures in the center plagued me throughout the painting – such a small part of the composition but also the linchpin to the entire scene for me. I really enjoyed the abstracted quality they had when I first quickly daubed them in toward the beginning and didn’t want to lose it, but felt a need to articulate them more as the piece moved forward. Their Hanboks changed color, went from unrecognizable blurs to solidifying into what I eventually could not unsee as Hershey’s Kisses, and then thankfully managed to strike a balance between the two.

The water to the left of the scene then became a source of ire as I struggled with how to portray the reflection of the palace quarters in the upper left and what elements, if any, to add to the water surface. I tried out numerous objects in that one spot until I settled on a statue inspired by images I’d seen of man-made islands in Korean waterways and Japanese Koi ponds. Various other tiny fires appeared and were extinguished until I reached a point where I had to put my brushes down and force myself not to make direct eye contact with the painting as I cleaned up for the night.

I’m aware of how overly dramatic and self-obsessive these posts may come across – and to be sure, they are – but this is an interesting aspect of a commitment to creating that I’ve had to accept. The ideas and emotions that spark new work come and go on their own unpredictable schedule, but the only reason the work gets done is because it feels so big and important to me. There is a childish glee that comes from anticipating the potential of a painting’s realization. I often think back to one night when I was 6 or 7 being struck with the brilliant idea of surrounding my bed with fake sewer walls so I could live inside a sewer like the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which I hurriedly started working on until realizing that Scotch tape and computer paper weren’t going to make my dreams come true. Every painting feels massive in the beginning – it’s potential limitless. There is a lot of fantasizing and tunnel vision before something gets started. The “blank canvas” has personally never been the hard part for me. As time goes on and the canvas starts to be increasingly defined, that definition starts threatening to become dead ends and lost enthusiasm. I’m starting to find that the key to a successful painting for me seems to be it’s continual reinvention – building up and destroying until you’re left with something you can’t wait to get back to tomorrow.

Maintaining this reinvention isn’t easy by any means, but as the saying goes, “nothing worth doing is”. Perhaps that’s true – then again eating pizza is easy and also worth doing. There’s an exception to every rule, I suppose.